Matthew J. Gold, OMS-III; Marshall Johnson, OMS-III; Alexandra Mathis, OMS-II; Shaheen Mehrara, OMS-III; Daniel Ruiz, OMS-IV; Caroline Houston, OMS-III; Jonathan Kalenik, OMS-III; Mayra Rodriguez, PhD, MPH

Author Affiliations

· Mayra Rodriguez, PhD, MPH, Edward Via College of Osteopathic Medicine – Auburn Campus

· Matthew J. Gold, OMS-III, Edward Via College of Osteopathic Medicine – Auburn Campus

· Marshall Johnson, OMS-III, Edward Via College of Osteopathic Medicine – Auburn Campus

· Alexandra Mathis, OMS-II, Edward Via College of Osteopathic Medicine – Auburn Campus

· Shaheen Mehrara, OMS-III, Edward Via College of Osteopathic Medicine – Auburn Campus

· Daniel Ruiz, OMS-IV, Edward Via College of Osteopathic Medicine – Auburn Campus

· Caroline Houston, OMS-III, Edward Via College of Osteopathic Medicine – Auburn Campus

· Jonathan Kalenik, OMS-III, Edward Via College of Osteopathic Medicine – Auburn Campus

Financial Disclosures

None reported.

Support

None reported.

Ethical Approval

The following study received IRB approval on 10/25/2021 by Edward Via College of Osteopathic Medicine (VCOM) IRB review board. IRB approval number: 1751555-4.

Informed Consent

All participants in this study were provided with informed consent prior to being presented with the survey questions used for data collection.

Correspondence Address

Address correspondence to Mayra Rodriguez, PhD, MPH, Edward Via College of Osteopathic Medicine – Auburn Campus, 910 S Donahue Rd, Auburn, AL 36832. Email: mrodriguez@auburn.vcom.edu

Author Contributions

Matthew J. Gold, OMS-III; Marshall Johnson, OMS-III; Shaheen Mehrara, OMS-III; Daniel Ruiz, OMS-IV; Jonathan Kalenik, OMS-III; Caroline Houston, OMS-III; Alexandra Mathis, OMS-II; and Mayra Rodriguez, PhD, MPH provided substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data. Matthew J. Gold, OMS-III and Marshall Johnson, OMS-III drafted the article or revised it critically for important intellectual content. Mayra Rodriguez, PHD, MPH gave final approval of the version of the article to be published; and all authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Mayra Rodriguez, Ph.D. for assisting and supporting this study. We also thank the Edward Via College of Osteopathic Medicine (VCOM) for the opportunity to present the abstract of this study at their 5th Annual Research Recognition Day at the VCOM-Auburn campus.

ABSTRACT

Context: There is little known about the lingering side effects of COVID-19 infection, and much of what is known has only been studied in older populations [1-3].

Objective: The objectives of this project strive to assess the most common lingering COVID-19 symptoms defined as greater than or equal to 4 weeks post-infection among young adults ages 18-30. In addition, duration of lingering symptoms will be examined between different races, genders, and medical history.

Methods: The following study received IRB approval by the VCOM IRB review board on October 25th, 2021 with the IRB approval number: 1751555-4. Participants (n = 138) completed a quantitative survey which included profile questions that were used in a descriptive analysis to evaluate what correlations exist between demographics and lingering COVID-19 symptoms. Measures include the comparison between social factors (i.e., employment status), genders, and race, specifically Hispanics versus non-Hispanics, with the longevity of the lingering COVID-19 symptoms (i.e., anosmia, fatigue, etc.) lasting greater than or equal to 4 weeks.

Results: The results revealed the top-five most common lingering symptoms in descending order: anosmia and ageusia (47 respondents), fatigue (17 respondents), chest pain (8 respondents), headaches (7 respondents) and cough (6 respondents). After comparing lingering symptoms between males and females, the data revealed that males may be more likely to experience lingering symptoms compared to females. Interestingly, both males and females reported that fatigue was the most common prominent symptom during initial infection, with anosmia and ageusia still remaining the most common lingering symptoms. When reviewing participants (126 individuals) with any medical history (i.e., allergies, asthma, anxiety, HTN, etc.) and participants (12 individuals) without medical history in the study, it was calculated that participants with any medical history seemed to be more likely to experience lingering COVID-19 symptoms compared to those without medical history. When comparing non-Hispanic and Hispanic responses, 5 Hispanic respondents out of 24 reported anosmia and ageusia lasting 4 weeks or greater compared to 27 non-Hispanic respondents out of 111 also experiencing anosmia and ageusia lasting 4 weeks or greater. Further studies are needed to assess the associations of lingering COVID-19 symptoms between Hispanic status and non-Hispanic status.

Conclusion: There are several other comparisons to be included comparing different genders, social factors, etc. This study was certainly limited by being self-surveyed which creates drawbacks to the study, as researchers did not confirm that those who completed a survey met the two criteria (tested positive via PCR or rapid antigen and age requirements 18-30 years old). The largest barrier faced was maintaining IRB compliance while also recruiting an adequate level of participants to meet the study criteria. The researchers held the ethical standard in abiding by IRB conduct.

INTRODUCTION

COVID-19 has become notorious for leaving unexplained symptoms months after initial infection. While there have been many studies that look at the “long haul COVID-19 symptoms” [4-6], few focus on the younger population [1-3]. This study breaks down a population between the ages of 18 to 30 even further. Within this age group, the study will analyze the different symptoms and those more likely to experience lingering symptoms between male and female, medical history versus no medical history, the difference in lingering symptoms between Hispanics versus non-Hispanics, and the perception this age group has on key topics that influence transmission. The broad goal of this study is to create data that will help public health officials and providers prepare for lingering symptoms post-COVID-19 and to understand the perception this group has on public health guidelines and efforts to prevent transmission.

There is little known about the lingering COVID-19 symptoms among young adults [1-3]. Commonly referred to as “long-haulers”, the population have an array of symptoms that have lasted for weeks, months, and now over a year [4-6]. These “long-haulers” have an average age of 40 years old [5-6]. This study investigates young adults between 18 to 30 years old to analyze the lingering COVID-19 symptoms if present. Currently, there is limited evidence on the medical and psychological effects of the post-infection lingering COVID-19 symptoms concerning the young adult population, as well as between various differentiations between groups of ethnicities and races [7-12].

This research began with a baseline of knowledge regarding symptoms of adults older than 30, children younger than 30, and pregnant women who all fell outside of the participants recruited for this project. An analysis published in November of 2020 with 400,000 participants studied the symptoms of pregnant women aging from 15-44 years of age [14]. It resulted in a finding that “pregnant women might be at increased risk for severe illness associated with coronavirus disease 2019” [14]. Another meta-analysis of 213 studies was published in June of 2021 researching the infection and transmission rate in children less than 18 year of age [15]. It concluded a “limited number of household transmission” due to children less than 18 years of age, however it failed to outline symptoms of the infected children [15]. Another prospective cohort study of 258,790 participants published in October of 2021 pooled data on symptoms and duration of children between the ages of 5 to 17 [16]. It resulted with “the most common symptoms being headache (1079 [62·2%] of 1734 children) and fatigue (954 [55·0%] of 1734 children)” [16]. This gave direction for symptoms to address in the current study, however it failed to research participants between the ages of 18-30. Lastly, a prevalence study of 2,299,666 child COVID-19 cases was published in March of 2021 which researched susceptibility of adolescents from the ages of 10 to 24 [17]. It resulted in a “significantly greater” prevalence of COVID-19 diagnosis for adolescents which was “contrary to previous findings that adolescents are less susceptible than older adults” [17]. This directed the project to target specific symptoms in adolescents and target the population aged between 18 to 30 years old. Our psychosocial questionnaire took root after a systematic review of 30 studies was published in July of 2020 [13]. The study resulted in a “COVID-19 vaccination intention during the first year of the pandemic ranging from 27.7% to 93.3%” [13]. This highlighted a perception of hesitancy towards vaccination, which in turn allowed us to target participants from the ages of 18 to 30 regarding this same topic.

Our objective was to understand the prevalence of COVID-19 symptoms in young adults during active infection and, of these symptoms, which tend to linger for weeks, months or years post-infection. We strived to compare the difference in prevalence and nature of lingering symptoms based on sex, past medical history, and race. We also intended to assess the psychosocial understanding and general public perception of the COVID-19 pandemic, including vaccinations, masks, legislation and mandates, politics, and media coverage [6-7].

METHODS

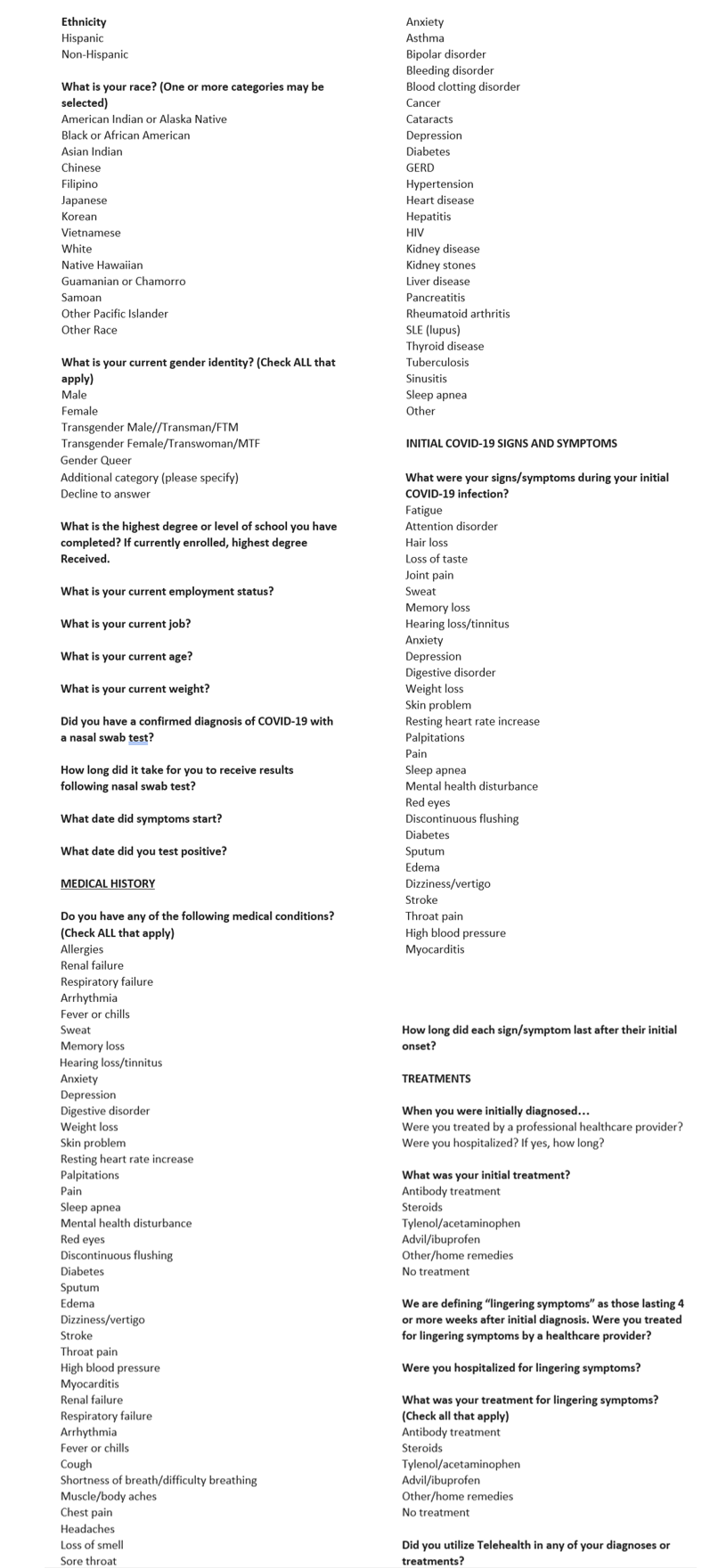

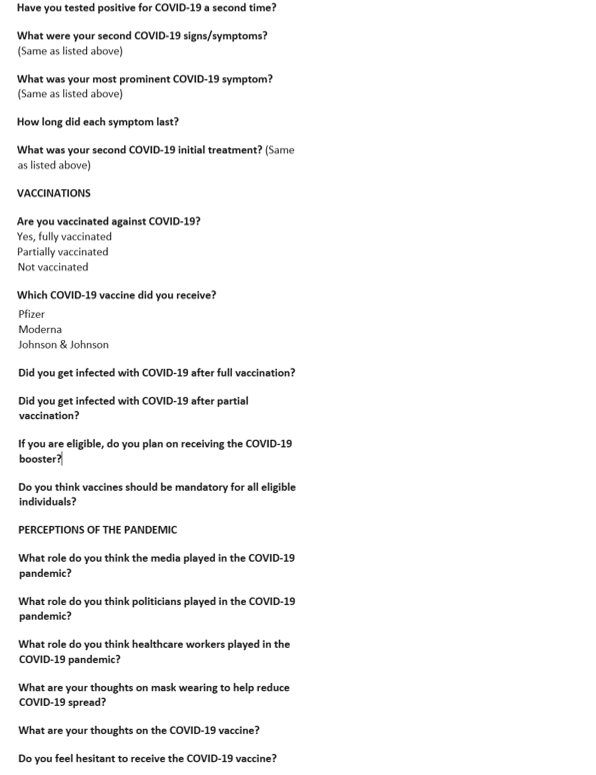

The following study received IRB approval by the VCOM IRB review board on October 25th, 2021 with the IRB approval number: 1751555-4. Participants (n=138) ages 18-30 who tested positive for COVID-19 via PCR or rapid antigen testing were asked to complete a survey. The survey asked participants to identify themselves based on age, race, gender identity, education level, employment status, weight, and pre-existing conditions. Questions were asked regarding how and when the participants tested positive for COVID-19, what symptoms they experienced during the initial infection, which of those symptoms lingered beyond the initial infection, whether or not they were vaccinated, and the degree of medical care they received during their illness. Participants were also asked some questions regarding their opinions of government response to the pandemic, media coverage of the pandemic, masking, vaccine mandates, and other social and public health aspects surrounding the COVID-19 pandemic [6-7]. Participants were sourced via social media distribution; researchers advertised the survey on their Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and Snapchat accounts and asked those aged 18-30 who had tested positive for COVID-19 to respond. No participant was contacted individually. The full-length survey that was provided to participants is included below.

RESULTS

When comparing lingering symptoms between males and females, it has been shown that 4 males out of 35 and 9 females out of 100 experienced lingering symptoms. However, the statistical significance of males to females experiencing lingering symptoms was not significant. The P-Value is 0.345 which shows the difference between genders is not statistically significant. Interestingly, both males and females reported that fatigue, loss of taste and loss of smell were the most prominent symptoms they experienced initially; men reported loss of taste more while women reported fatigue more as their most prominent symptom. Furthermore, anosmia and ageusia still remain the most common lingering symptoms in both groups with most reporting the time of these lingering symptoms to be 2-4 weeks versus 7-14 days of fatigue and 3-5 days of muscle or body aches. There were 100 females and 35 males who participated in the survey (3 participants did not reveal gender) which may have been due to women’s increased level of health consciousness or due to the differences in desire to participate in a study involving one’s health status.

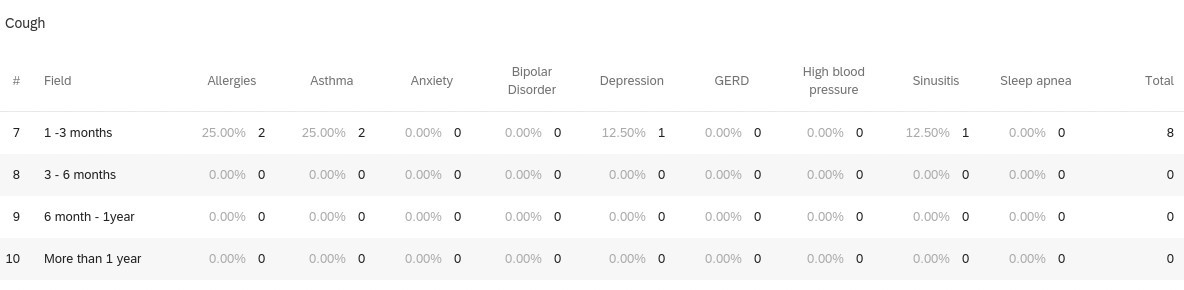

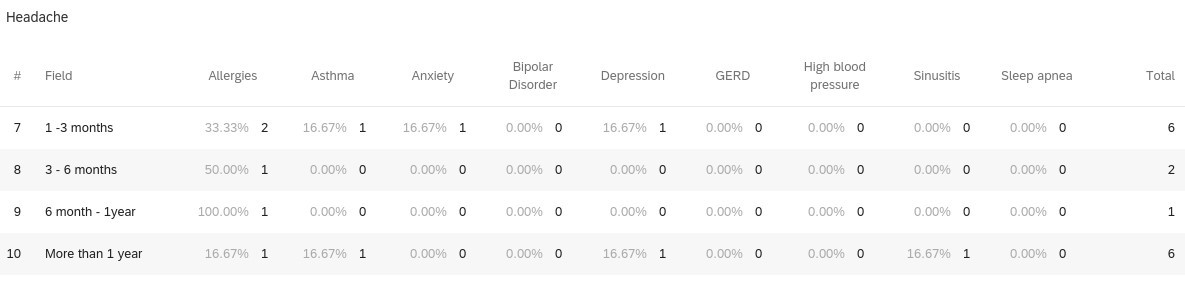

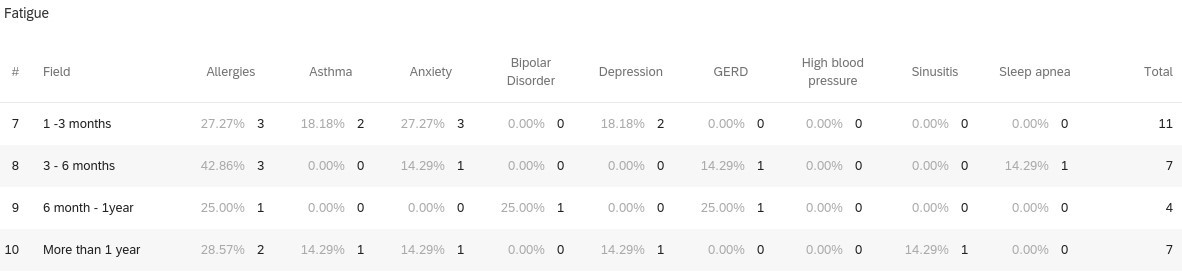

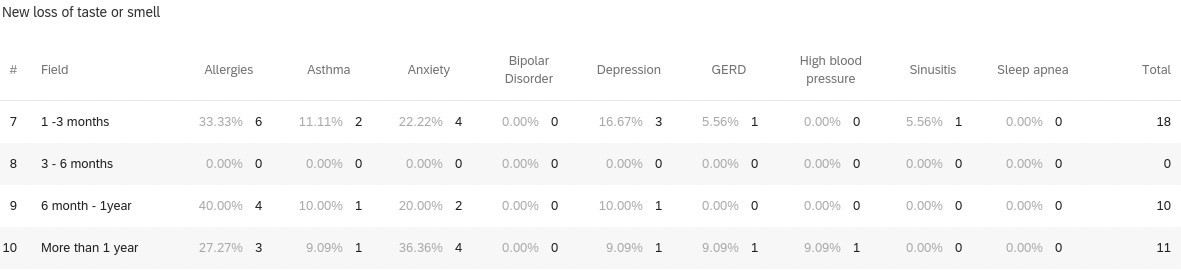

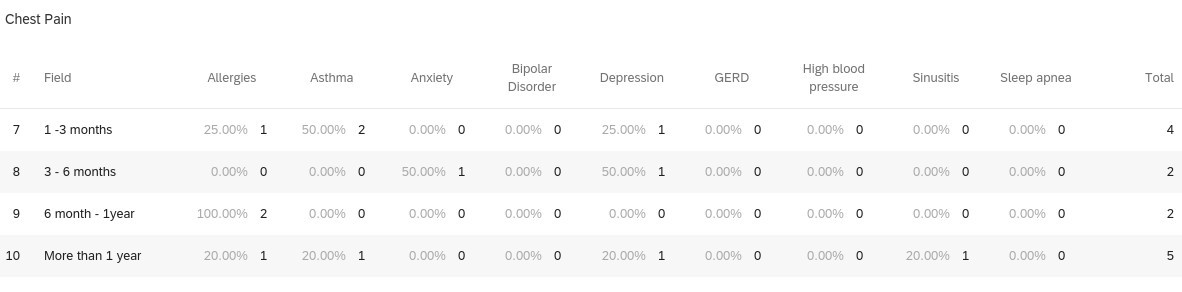

When reviewing 126 individuals with any medical history (i.e., allergies, asthma, anxiety, HTN, etc.) and 12 individuals without medical history in the study, it was calculated that participants with any medical history seemed to be more likely to experience lingering COVID-19 symptoms compared to those without medical history. Those with allergies (unspecified) in their past medical history seemed to experience lingering COVID-19 symptoms more than other medical histories. Participants with allergies most commonly reported anosmia and ageusia for lingering symptoms. Another observation, individuals with depression reported anosmia and ageusia most commonly for lingering symptoms as well. Interestingly, when comparing those with asthma (19 respondents) and without asthma (119 respondents), those with asthma may be more likely to experience lingering symptoms compared to those without asthma. Participants with asthma also most commonly reported anosmia and ageusia for lingering symptoms (Figures 1-5).

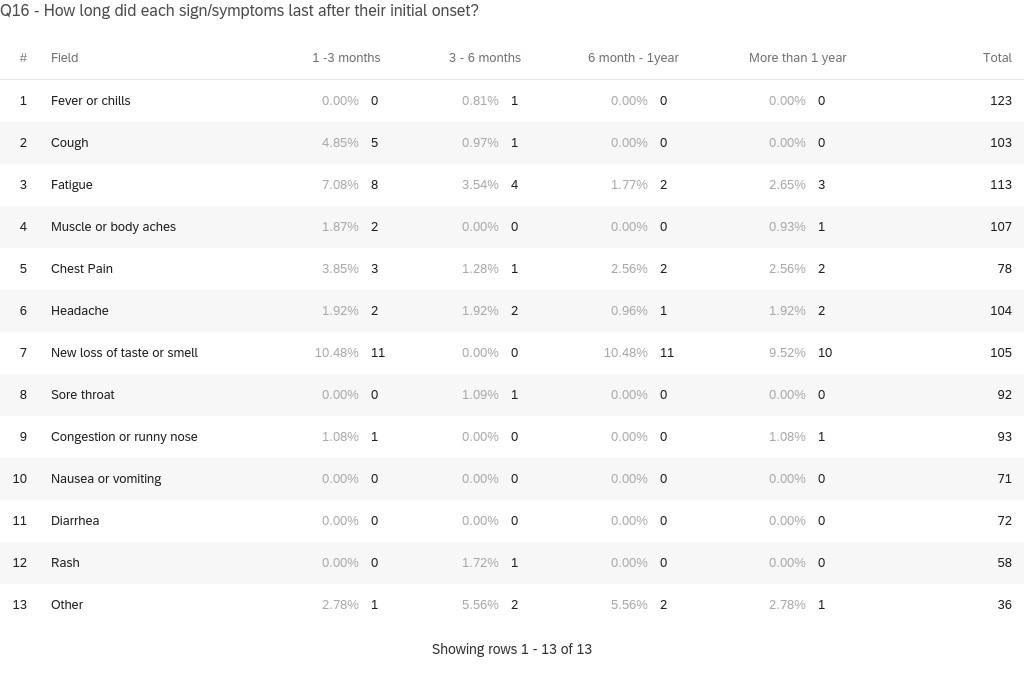

The top-five most common lingering symptoms of young adults were (in descending order): anosmia and ageusia (27 respondents and 20 respondents, respectively), fatigue (17 respondents), chest pain (8 respondents), headaches (7 respondents), and cough (6 respondents) (Figure 6). Interestingly, these symptoms are consistent with previous meta-analyses discussing long-term COVID-19 symptoms and a cross-sectional study emphasizing hyposmia and hypogeusia which showed similar incidence in symptomatology [18-19].

When looking at lingering symptoms between Hispanics (24 participants) and non-Hispanics (111 participants), 5 Hispanics reported anosmia and ageusia lasting 4 weeks or greater compared to 27 non-Hispanics that reported anosmia and ageusia lasting 4 weeks or greater. This is consistent with a study of a population in Mexico reporting anosmia as one of their recovering symptoms [20]. Likewise, when looking at lingering symptoms such as fatigue and headache, 16 non-Hispanic participants experienced fatigue lasting 4 weeks or greater and 6 non-Hispanic participants experienced headache lasting 4 weeks or greater while none of the Hispanic participants experienced fatigue or headache lasting 4 weeks or greater. In this study, younger Hispanics may be less likely to experience lingering symptoms compared to non-Hispanics [9].

To understand the psychosocial effects surrounding COVID-19, participants’ responses were recorded and analyzed on multiple topics. Assessing whether respondents would get the COVID-19 booster shot if eligible: 177 responses revealed 58.12% answered “yes”, while 41.88% of responses answered “no”. Assessing whether vaccines should be mandatory for all eligible citizens: 120 responses revealed 35.0% answered “yes”, while 65.0% of responses answered “no”. Assessing if respondents felt hesitant towards receiving the COVID-19 vaccine: 73 responses revealed 60.3% did not feel hesitant, 28.8% did feel hesitant, 6.8% felt hesitant towards the vaccine booster but not hesitant towards the vaccine, and 4.1% were hesitant until FDA approval of the vaccine [7, 8,10,13]. The range of hesitancy, between 28.8% feeling hesitant and 60.3% not feeling hesitant, towards intention of vaccination was consistent with previous studies showing a “COVID-19 vaccination intention during the first year of the pandemic ranging from 27.7% to 93.3%” [13].

DISCUSSION

When looking at the results, the study demonstrated that young adults do face lingering symptoms of COVID-19. Many of these symptoms reported by participants of this study have been listed in several other studies, however there seems to be consistency in the young adult population with the general adolescent and adult population [1-2,4-6, 9, 12, 16, 18-20]. It’s also important to note that the results showed that a significant portion of young people do not find it in their interest to receive the booster shot [10]. The self completion surveys set limitations to the study, as researchers did not confirm that those who completed a survey met the prerequisite criteria. The largest barrier faced was to maintain IRB compliance while recruiting an adequate level of participants to meet the study criteria. The IRB refrained the researchers from contacting or answering questions of participants individually. This inability to answer individual questions, such as issues with the link, creates a question of how to maintain ethical standards of recruitment without suppressing an investigator’s ability to seek the appropriate population. This further challenges researchers in following ethical protocol while maintaining engagement with the population in question.

CONCLUSIONS

Findings in this study demonstrated lingering COVID-19 symptoms that are not usually found in the young population such as chest pain, even among males. Headaches were not as commonly reported as lingering symptoms, but there may be an association more towards the beginning of the COVID-19 illness, as seen in adolescents [16]. This study also demonstrated what was previously known about pre-existing conditions; those with extensive medical histories may be more likely to experience lingering symptoms. Furthermore, it shows there is a long way to go to reach the young population to make them aware of the effectiveness and importance of boosters. We encourage other investigators to further research how the Hispanic population perceived the Coronavirus differently than the general population and the effects it has had in their socioeconomic status. Further research needs to be done on how the most vulnerable populations have been affected by the virus and their perceptions of the vaccine. This guides providers and public health officials in maximizing resources to further prevent wave levels of transmission.

REFERENCES

1. Wanga V, Chevinsky JR, Dimitrov LV, et al. “Long-Term Symptoms Among Adults Tested for SARS-CoV-2 — United States, January 2020–April 2021.” MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2021;70:1235–1241. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7036a1

2. Zarei, M, Bose, D, Nouri-Vaskeh, M, Tajiknia, V, Zand, R, Ghasemi, M. Long-term side effects and lingering symptoms post COVID-19 recovery. Rev Med Virol. 2021;e2289. doi:10.1002/rmv.2289

3. Taquet, Maxime, et al. “Incidence, Co-Occurrence, and Evolution of Long-COVID Features: A 6-Month Retrospective Cohort Study of 273,618 Survivors of Covid-19.” PLOS Medicine, vol. 18, no. 9, 28 Sept. 2021, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003773.

4. Alwan NA, Johnson L. Defining long COVID: Going back to the start. Med (N Y). 2021;2(5):501-504. doi:10.1016/j.medj.2021.03.003

5. Fernández-de-Las-Peñas, César, et al. “Defining post-COVID symptoms (post-acute COVID, long COVID, persistent post-COVID): an integrative classification.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18.5 (2021): 2621.

6. Rubin R. As Their Numbers Grow, COVID-19 “Long Haulers” Stump Experts. JAMA. 2020;324(14):1381–1383. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.17709

7. Mental Health and Covid-19.” World Health Organization, World Health Organization, 27 Feb. 2022, https://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/health-emergencies/coronavirus-covid-19/publications-and -technical-guidance/noncommunicable-diseases/mental-health-and-covid-19.

8. Mental Health and Psychosocial Considerations during the COVID-19 Outbreak . WHO, 18 Mar. 2020, https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/mental-health-considerations.pdf.

9. Adams SH, Park MJ, Schaub JP, Brindis CD, Irwin CE Jr. Medical Vulnerability of Young Adults to Severe COVID-19 Illness-Data From the National Health Interview Survey. J Adolesc Health. 2020 Sep;67(3):362-368. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.06.025. Epub 2020 Jul 13. PMID: 32674964; PMCID: PMC7355323.

10. Adams SH, Schaub JP, Nagata JM, Park MJ, Brindis CD, Irwin CE Jr. Young Adult Perspectives on COVID-19 Vaccinations. J Adolesc Health. 2021 Sep;69(3):511-514. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.06.003. Epub 2021 Jul 14. PMID:34274212; PMCID: PMC8277980.

11. Carfì A, Bernabei R, Landi F; Gemelli Against COVID-19 Post-Acute Care Study Group. Persistent Symptoms in Patients After Acute COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;324(6):603-605. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.12603

12. Carvalho-Schneider, Claudia, et al. “Follow-up of Adults with Noncritical COVID-19 Two Months after Symptom Onset.” Clinical Microbiology and Infection, vol. 27, no. 2, Feb. 2021, pp. 258–263., https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2020.09.052.

13. Al-Amer, R., Maneze, D., Everett, B., Montayre, J., Villarosa, A. R., Dwekat, E., & Salamonson, Y. (2022). COVID-19 vaccination intention in the first year of the pandemic: A systematic review. Journal of

Clinical Nursing, 31,62– 86. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.15951

14. Zambrano LD, Ellington S, Strid P, et al. Update: characteristics of symptomatic women of reproductive age with laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection by pregnancy status: United States, January 22–October 3, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020 Nov 6;69(44):1641-7.

15. Zhu Y, Bloxham CJ, Hulme KD, et al. A meta-analysis on the role of children in severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 in household transmission clusters. Clin Infect Dis. 2021 Jun 15;72(12):e1146-53

16. Molteni, Erika, et al. “Illness Duration and Symptom Profile in Symptomatic UK School-Aged Children Tested for SARS-CoV-2.” Lancet Child Adolesc Health 2021, 3 Aug. 2021, doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(21)00198-X.

17. Rumain B, Schneiderman M, Geliebter A. Prevalence of COVID-19 in adolescents and youth compared with older adults in states experiencing surges. PLoS One. 2021 Mar 10;16(3):e0242587. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0242587. PMID: 33690600; PMCID: PMC7946189.

18. Lopez-Leon, S., Wegman-Ostrosky, T., Perelman, C. et al. More than 50 long-term effects of COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep 11, 16144 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-95565-8

19. Nouchi, A., Chastang, J., Miyara, M. et al. Prevalence of hyposmia and hypogeusia in 390 COVID-19 hospitalized patients and outpatients: a cross-sectional study. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 40, 691–697 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10096-020-04056-7

20. Galván-Tejada CE, Herrera-García CF, Godina-González S, Villagrana-Bañuelos KE, Amaro JDL, Herrera-García K, Rodríguez-Quiñones C, Zanella-Calzada LA, Ramírez-Barranco J, Avila JLR, Reyes-Escobedo F, Celaya-Padilla JM, Galván-Tejada JI, Gamboa-Rosales H, Martínez-Acuña M, Cervantes-Villagrana A, Rivas-Santiago B, Gonzalez-Curiel IE. Persistence of COVID-19 Symptoms after Recovery in Mexican Population. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020 Dec 14;17(24):9367. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17249367. PMID: 33327641; PMCID: PMC7765113.

FIGURES, TABLES, APPENDICES, AND VIDEOS

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 4

Figure 5

Figures 1-5 demonstrates the breakdown of individuals with past medical history experiencing the top-5 most common lingering (greater than or equal to 1 month) COVID-19 symptoms.

Figure 6

Figure 6 reveals the top lingering (greater than or equal to 1 month) COVID-19 symptoms and the total is the amount of participants who reported the pertinent symptom during infection at any point of their illness.