Shanes, A, OMS II*, Shecter, I, OMS II*, Bograkos, W, M.A., D.O.

University of New England College of Osteopathic Medicine, Biddeford, Maine

*co-authors

Introduction: The opioid epidemic poses a huge public health concern nationwide. The State of Vermont is invested in curbing opioid-related fatalities through harm reduction and prevention programming. Infrastructure to promote safer practices includes medication assisted treatment (MAT) facilities, naloxone distribution sites, and access to buprenorphine waivered physicians. Additionally, emergency medical services (EMS) are a highly utilized entity that administers naloxone in life-threatening situations. Analyzing these resources with Geographic Information Systems (GIS) allows for the visualization of resource allocation throughout the state. The State of Maine had previously set precedent by utilizing GIS to analyze their opioid-related resources, which led to better- informed recommendations for practices. Utilizing GIS to analyze Vermont’s distribution of resources will allow for the identification of high-risk communities as well as lending insight into whether resources are reaching those communities in need.

Methods: The data analyzed in this study were sourced from publicly available data sets including the Vermont Department of Public Health and the United States Census. All data, with the exception of median household income, were organized by county and normalized by population. Data sets include median household income, accidental and undetermined opioid-related fatalities, number of buprenorphine waivered physicians, number of patients administered naloxone by EMS, medication assisted treatment utilization for opioid use disorder, and naloxone distribution sites. Data sets were analyzed using Microsoft Excel and mapped using ArcGIS Online software.

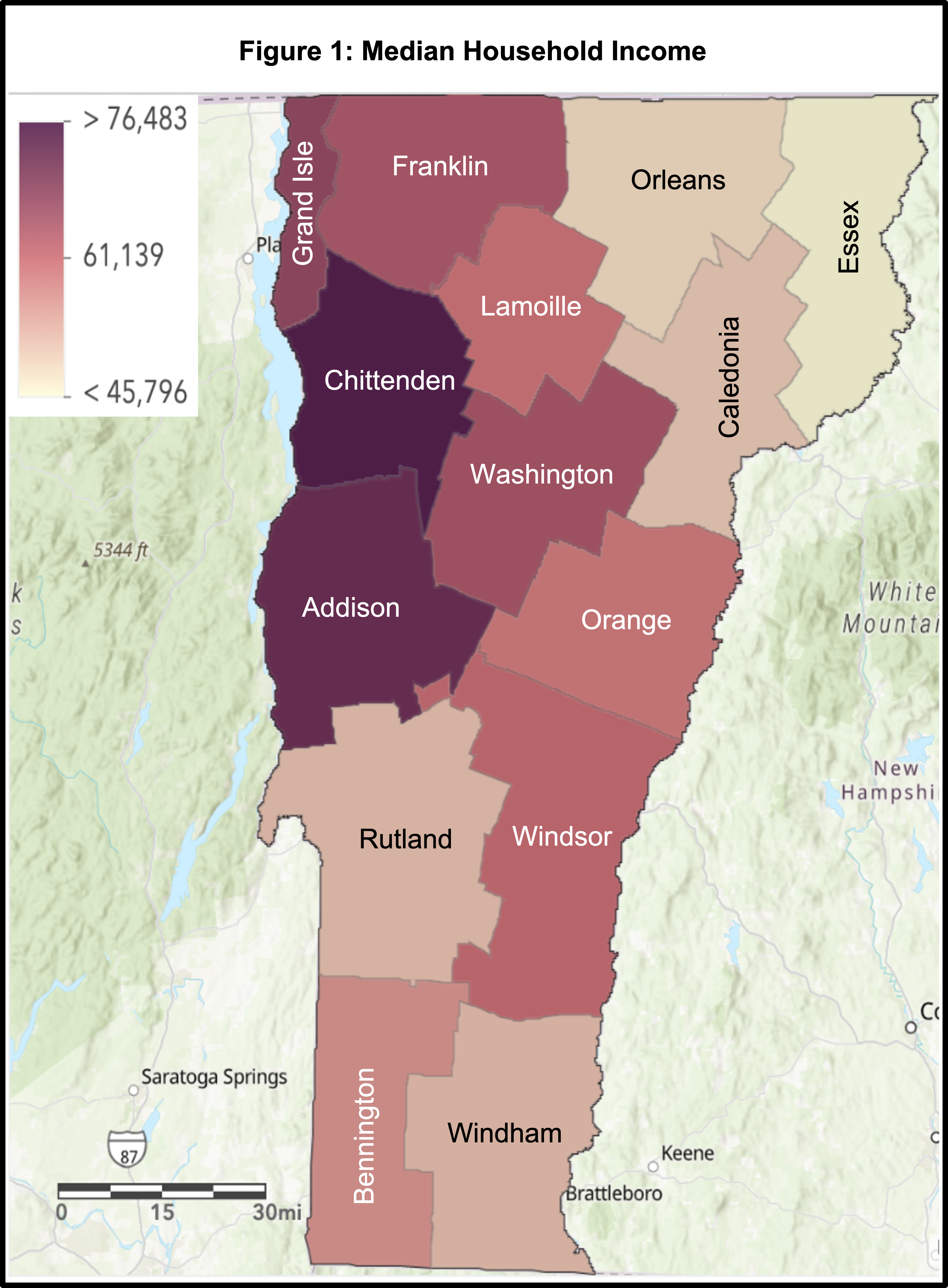

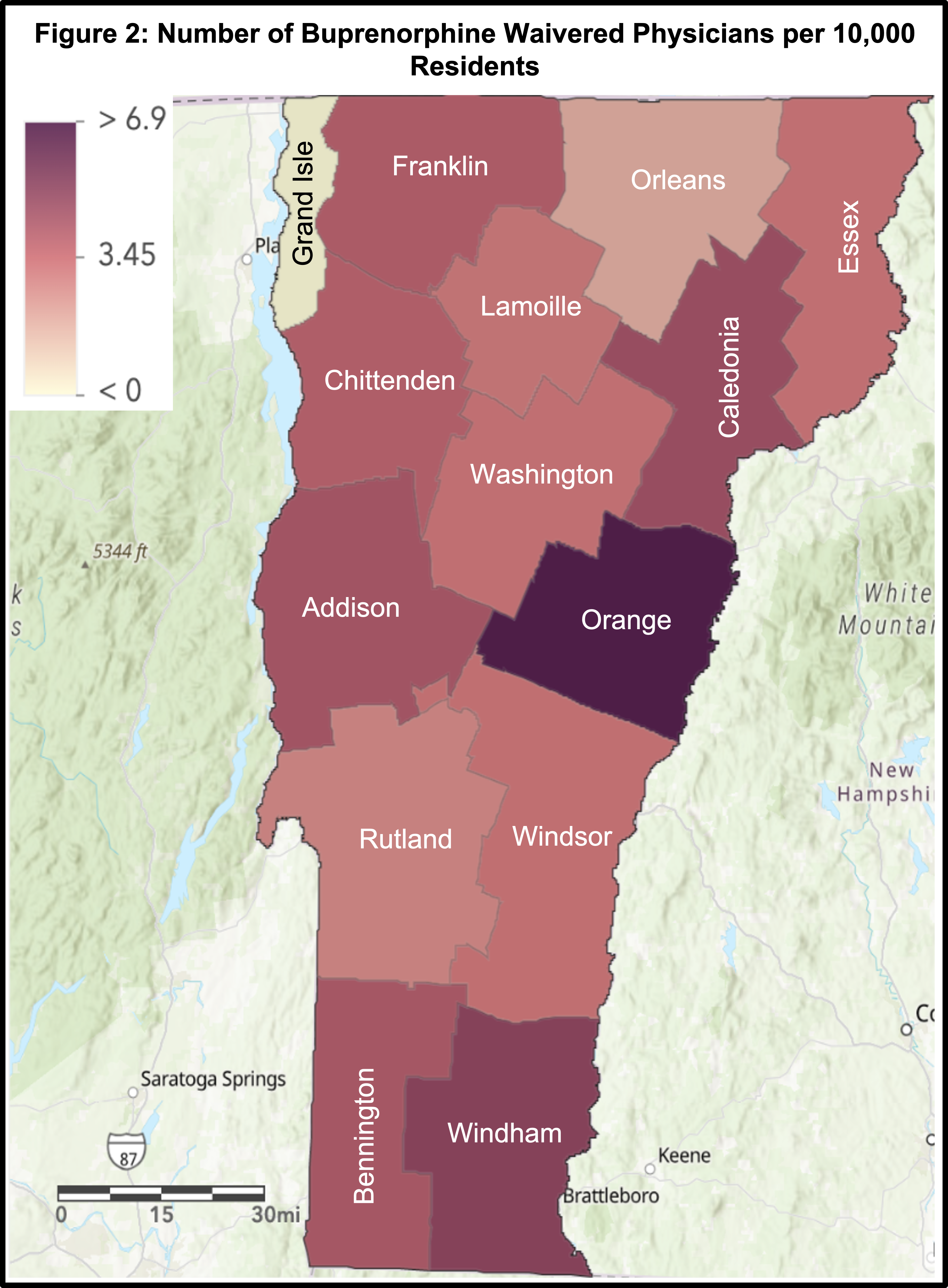

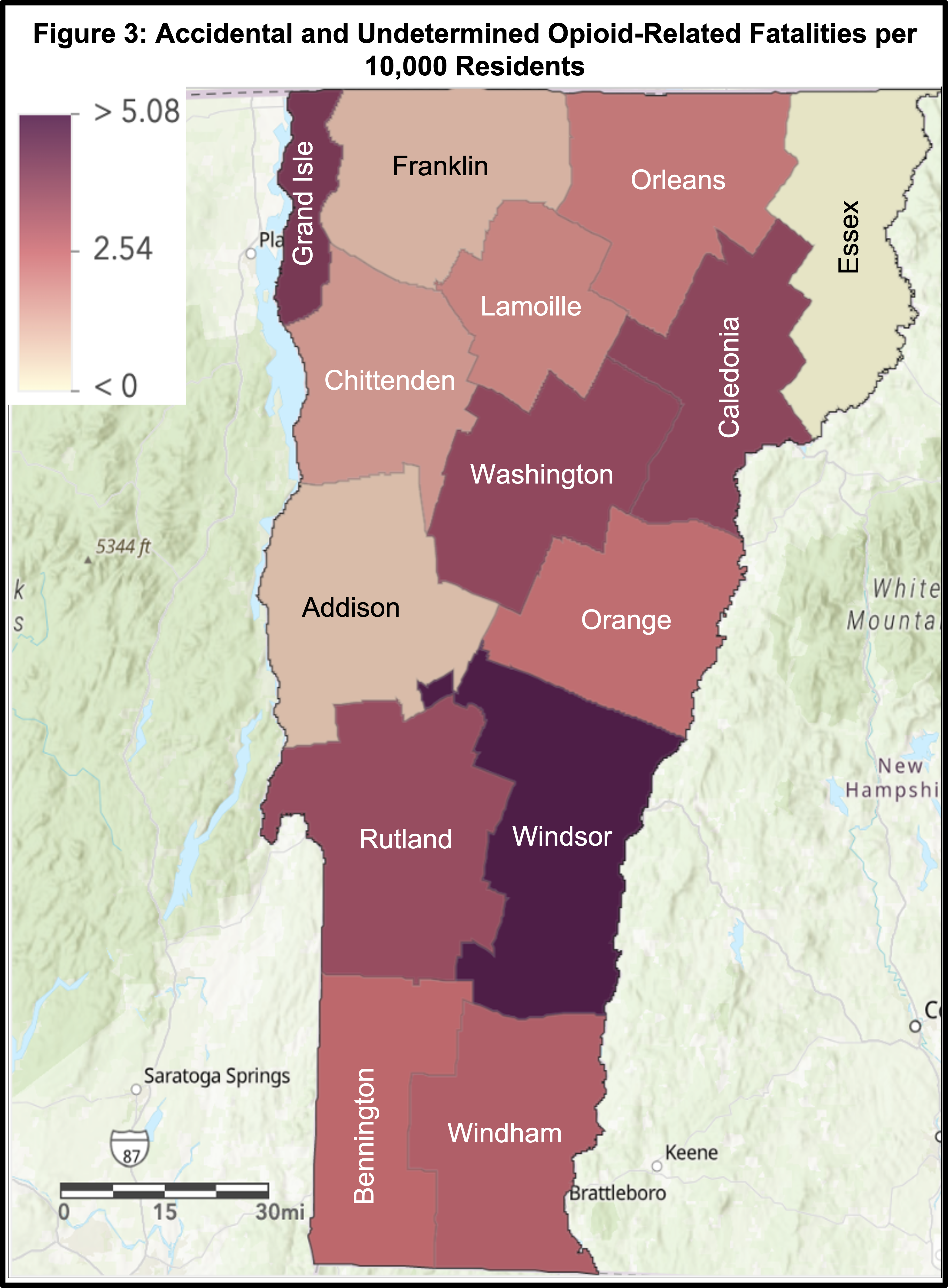

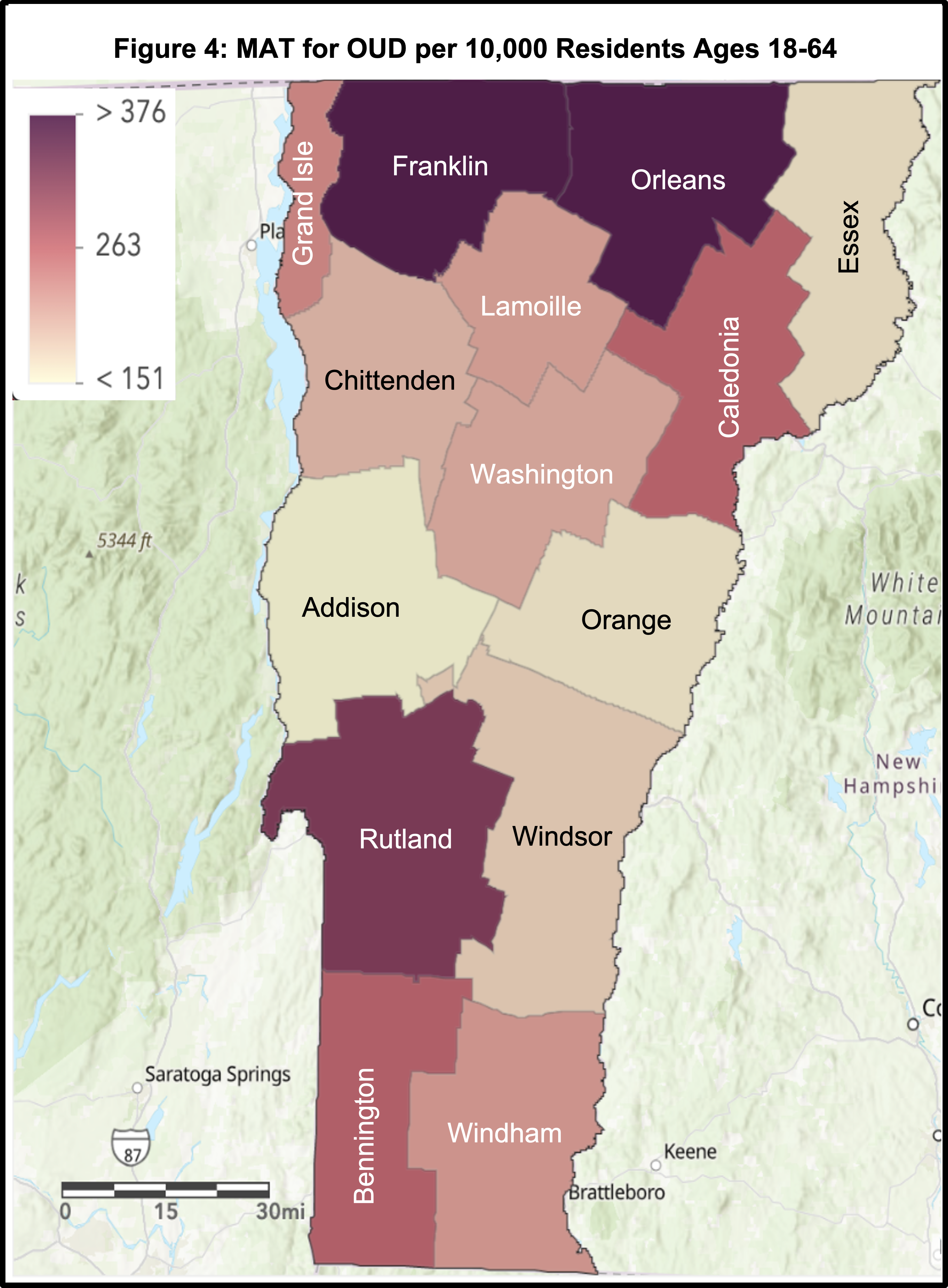

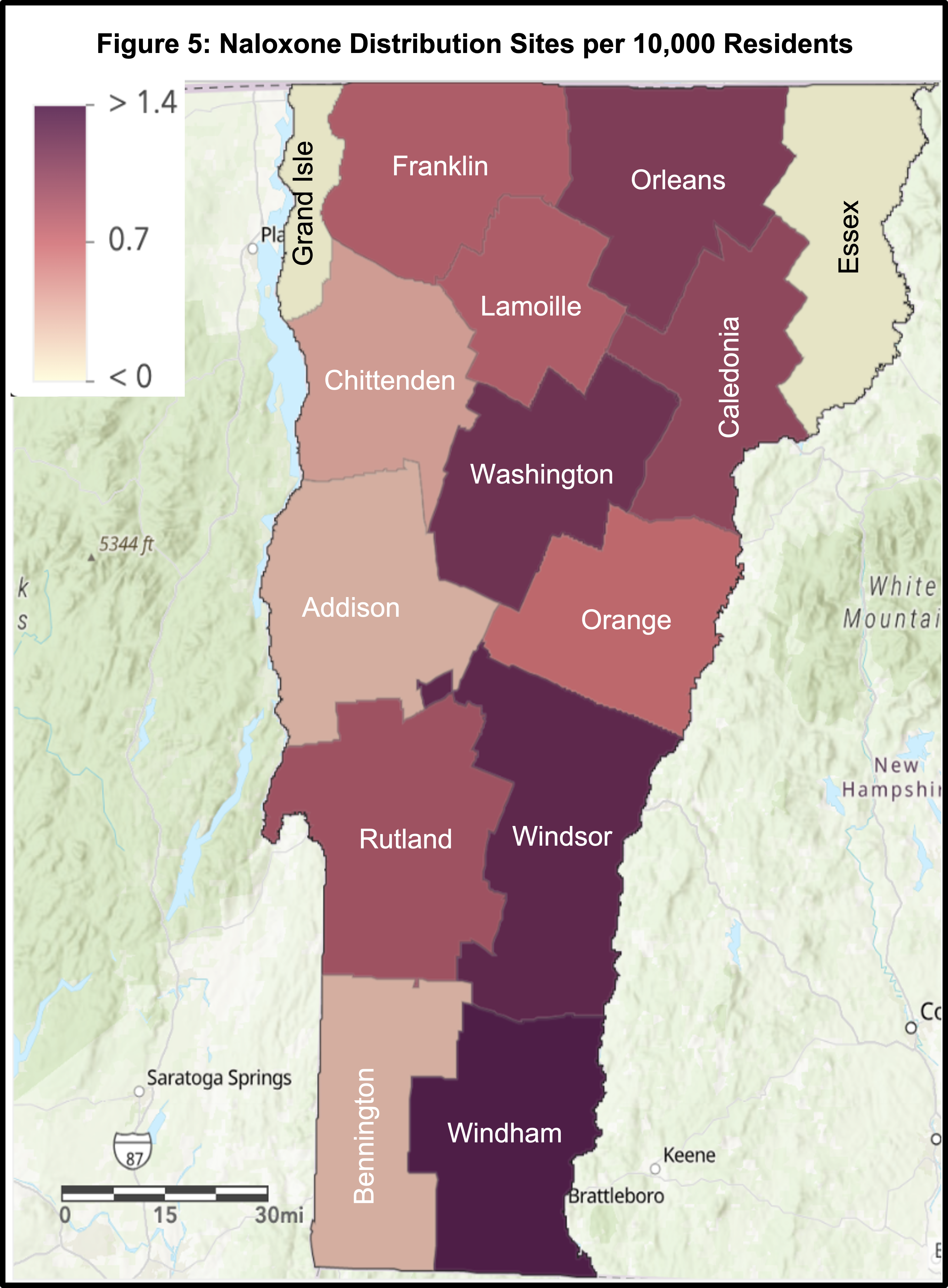

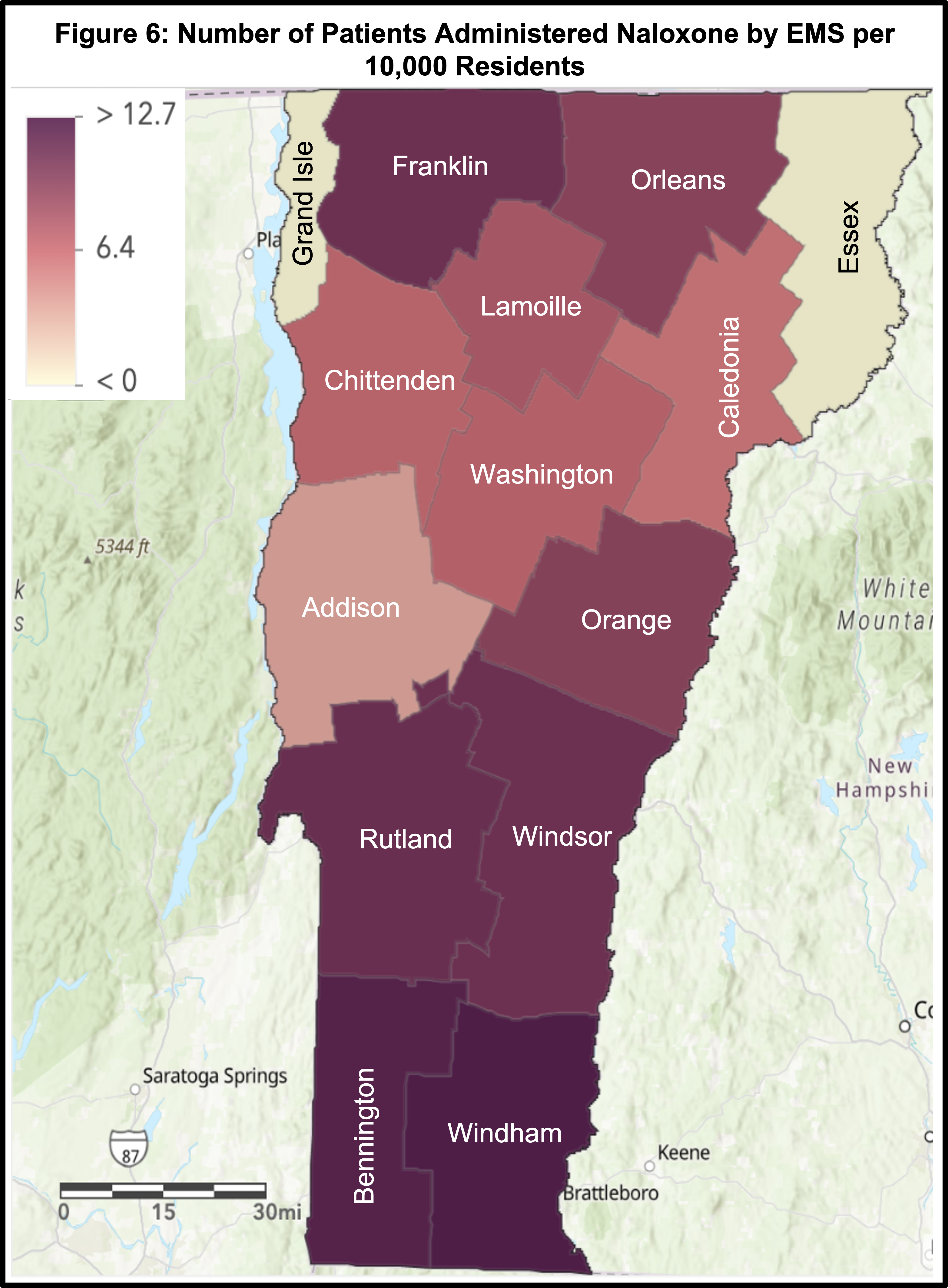

Results: Relevant data were analyzed and mapped utilizing ArcGIS software. Addison and Chittenden Counties are the two wealthiest counties in Vermont, both with an above average number of buprenorphine waivered physicians (4.35 and 3.91 respectively) and below average opioid-related fatalities (0.8 and 1.6 respectively) (Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3). Windsor and Grand Isle Counties have above average median household incomes but the highest opioid-related fatalities (5.1 and 4.2 respectively). Both counties also have a below average number of buprenorphine waivered physicians (3.27 and 0 respectively). Orange County has a below average median household income and opioid-related fatality rate (2.4), but an above average number of buprenorphine waivered physicians (6.92). The majority of counties with above average opioid-related fatalities have below average numbers of buprenorphine waivered physicians and MAT usages, while also having above average naloxone distribution sites (Figure 4, Figure 5). A majority of counties with below average opioid-related fatalities have higher numbers of buprenorphine waivered physicians, and lower than average numbers of naloxone distribution sites. Franklin County has above average numbers of buprenorphine waivered physicians (4.05), MAT usages (3.76), naloxone distribution sites (0.8), EMS naloxone administrations (11.1), and one of the lowest rates of opioid-related fatalities (1.0) (Figure 6). All data discussed, excluding median household income, are normalized per 10,000 residents.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 4

Figure 5

Figure 6

Discussion: Although wealth likely plays a role in access to resources, Windsor and Grand Isle Counties demonstrated that having an above average median household income does not necessarily correlate with below average opioid-related fatalities. The opposite also holds true, as represented by Orange County, which has a below average median household income as well as below average opioid-related fatalities. Therefore, it is unclear whether a correlation between wealth and the incidence of opioid-related fatalities exists. While wealth may not decrease the rate of opioid-related fatalities, we note that the number of buprenorphine waivered physicians may. Counties with above average numbers of buprenorphine waivered physicians correlated with below average opioid-related fatalities. Conversely, counties with above average opioid-related fatalities generally have a below average number of buprenorphine waivered physicians. We recommend counties increase their number of buprenorphine waivered physicians, as this seems to be associated with a reduced rate of opioid-related fatalities. An additional finding from our analysis indicates that the number of naloxone distribution sites may not have a direct impact on decreasing opioid-related fatalities as many might expect. Having an above average number of naloxone distribution sites in a county does not consistently correlate with that county having a reduced incidence of opioid-related fatalities. While we acknowledge access to this resource does mitigate death, we hypothesize that either underutilization or improper use of naloxone may be occurring. We recommend increasing educational resources regarding naloxone distribution locations and its proper usage to obtain the intended results. Lastly, our analysis showed Franklin County has an above average number of buprenorphine waivered physicians, MAT usages, naloxone distribution sites, and EMS naloxone administrations and has one of the lowest rates of opioid-related fatalities. We recommend other counties in the state look to Franklin County as an example of how diversity in resources can lead to lower rates of opioid-related fatalities.

Conclusion: This study used GIS to visualize how resources allocated to combat the opioid epidemic relate to the rate of opioid-related fatalities in the State of Vermont. Our analysis recommends counties increase their number of buprenorphine waivered physicians and identify barriers to proper naloxone distribution and use. Further research investigating naloxone distribution site advertisement, access by community members, and educational materials is warranted to better understand our findings. In all, our analysis suggests resources related to maintenance therapy, rather than rescue therapy, may have a better impact on reducing the rate of opioid-related fatalities.

Acknowledgment: We would like to acknowledge the University of New England College of Osteopathic Medicine and especially thank Dr. Bograkos who serves as an Advisor to the UNE COM chapter of the World Association for Disaster and Emergency Medicine.

Resources:

- “Buprenorphine Practitioner Locator” Accessed July 2021. https://www.samhsa.gov/medication-assisted-treatment/practitioner-program-data/treatment-practitioner-locator?field_bup_state_value=53&field_bup_lat_lon_proximity%5Bvalue%5D=25&field_bup_lat_lon_proximity%5Bsource_configuration%5D%5Borigin_address%5D=&field_bup_city_value=&page=0

- Jones, M.R., Viswanath, O., Peck, J. et al. A Brief History of the Opioid Epidemic and Strategies for Pain Medicine. Pain Ther 7, 13–21 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40122-018-0097-6

- “Median Household Income” Dec. 2020. https://www.healthvermont.gov/sites/default/files/documents/pdf/ADAP_RPP_Data_AddisonCty.pdf

- “Medication Assisted Treatment in Vermont Hubs and Spokes Quarterly Report” April 2021. https://www.healthvermont.gov/sites/default/files/documents/pdf/ADAP-MAT-HubSpoke-QuarterlyReport.pdf

- “Naloxone Data Brief” Dec. 2020. https://www.healthvermont.gov/sites/default/files/documents/pdf/ADAP_Naloxone_Data_Brief_0.pdf

- “Narcan Distribution Sites in Vermont” Accessed July 2021. https://www.healthvermont.gov/emergency/injury/opioid-overdose-prevention-naloxone

- “Opioid-Related Fatalities Among Vermonters” Mar. 2021. https://www.healthvermont.gov/sites/default/files/documents/pdf/ADAPOpioidFatalityDataBrief2020_Final.pdf

- Stopka TJ, Jacque E, Kelso P, et al. The opioid epidemic in rural northern New England: An approach to epidemiologic, policy, and legal surveillance. Prev Med. 2019;128:105740. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2019.05.028