Grace Bunemann MS41, Madison Greco MS41

1Campbell University School of Osteopathic Medicine

Abstract

Introduction

High-Altitude Illness and its related disorders (Acute Mountain Sickness, High-Altitude Cerebral Edema, and High-Altitude Pulmonary Edema) have often been documented to occur at altitudes over 2100m/7000ft. However, the onset of symptoms varies by person, rate of ascent, and altitude reached. The pathophysiology of high-altitude illness involves hypobaric hypoxia, cerebral vasodilation, and vasodilatory mediators such as bradykinin and nitric oxide. Angioedema is swelling of the skin and mucous membranes similarly characterized by vasodilatory reactions involving mast cells and bradykinin. A specific subtype of angioedema, called inducible urticaria, results from physical stimuli such as cold or pressure. While angioedema of the lips has not been documented as a result of altitude, multiple case studies have shown peripheral edema (including facial swelling) to occur with Acute Mountain Sickness.

Case

We present the case of a 27 year old female without significant past medical history who developed altitude induced angioedema of the lips on day 4 of her ascent of Mt. Kilimanjaro, at an elevation of approximately 3,800m/12,500ft.

Conclusion

Angioedema of the lips is an under-reported reaction associated with high altitude. While high-altitude illness and its complications have been heavily documented, this reaction has never been described in medical literature as a result of altitude.

Introduction

High-Altitude Illness and its related disorders have often been documented to occur over 2100m/7000ft. However, the onset of symptoms varies by person, rate of ascent, and altitude reached. The typical forms of High-Altitude Illness include Acute Mountain Sickness (AMS), High-Altitude Cerebral Edema (HACE), and High-Altitude Pulmonary Edema (HAPE)1. The pathophysiology of high-altitude illness involves hypobaric hypoxia, cerebral vasodilation, and vasodilatory mediators such as bradykinin and nitric oxide1. As a rule, illness occurring at high altitude should be attributed to the altitude until proven otherwise. Thus, as a reaction to high-altitude, angioedema of the lips is an under-reported reaction in the medical literature.

Angioedema is swelling of the skin and mucous membranes characterized by vasodilatory reactions involving mast cells and bradykinin2. A specific subtype of angioedema, called inducible urticaria, results from physical stimuli such as cold or pressure2,3. While peripheral edema including facial swelling is not a symptom of AMS per the Lake Louise AMS scoring criteria, it has been reported to occur with AMS4. Due to the similar pathophysiology of High-Altitude Illness and angioedema, it is possible that angioedema of the lips is a true reaction to altitude and not just an associated manifestation.

Case Description

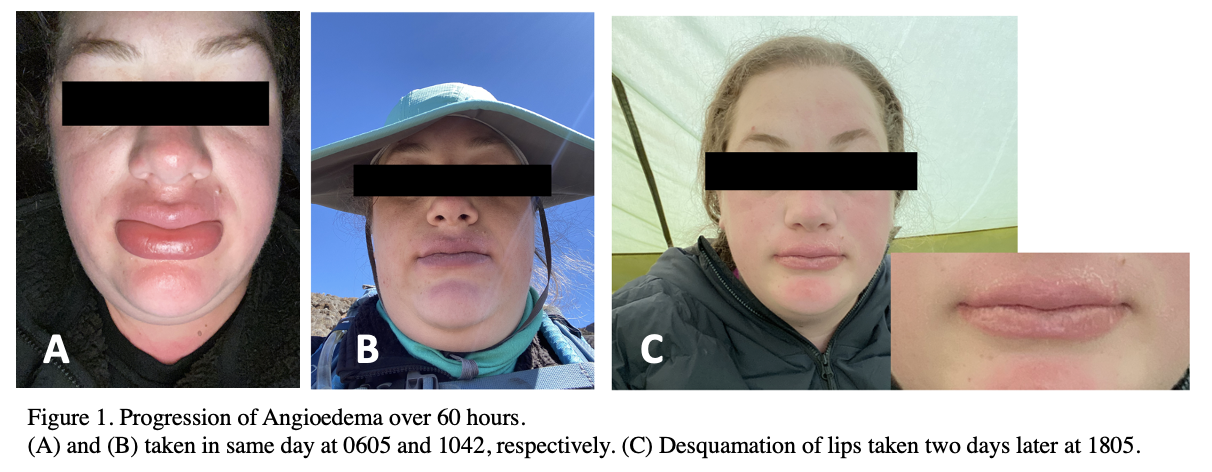

A 27-year-old female without significant past medical history reported waking up with significantly enlarged lips on day 4 of hiking Mt. Kilimanjaro, sleeping elevation of 3,800m/12,500ft. On the afternoon of the third day, the patient reported experiencing perioral pain, burning, and itching sensations. Petroleum jelly was applied to offset the symptoms and a gaiter was worn for elemental protection of the neck and lower face; neither intervention resulted in symptom alleviation. The patient reported consulting their lead and assistant guides individually (with 25 & 10 years of experience respectively) about lip swelling. The guides reported this was a regular occurrence and that it would resolve in a few hours after beginning hiking. As illustrated via in the patient’s pictures below, the swelling resolved within hours.

No further instances of lip swelling were reported. The patient continued use of petroleum jelly and gaiter for elemental protection. Patient reported desquamation of lips over the following week. Of note, the patient adhered to a prophylaxis regimen for high-altitude excursions: acetazolamide and antimalarial agents. On average, the patient’s water consumption was the recommended 4 L of water daily with electrolyte replenishment tablets added to 2 L in order to offset the diuretic effect of acetazolamide.

Discussion

High-Altitude Illness and its related disorders have been documented since well before Dr. Thomas Ravenhill first clinically classified the disease in 19135. The typical forms of High-Altitude Illness include Acute Mountain Sickness (AMS), High-Altitude Cerebral Edema (HACE), and High-Altitude Pulmonary Edema (HAPE)1. Of these, AMS is the most common1. Symptoms of high-altitude disorders usually occur over 2100m/7000ft, however onset of symptoms varies by person, the rate of ascent, and altitude reached1. As a rule, illness occurring at high altitude should be attributed to the altitude until proven otherwise1.

The primary pathophysiology of AMS is thought to involve hypobaric hypoxia; however other mechanisms such as hypoxemia-induced cerebral vasodilation or vasodilatory mediators such as nitric oxide, are thought to be involved1. HACE and HAPE are more severe, potentially fatal forms of High-Altitude Illness. HACE is characterized by global encephalopathy thought to be caused by cytotoxic edema or vasogenic edema1. Other contributing factors include impaired cerebral autoregulation, sustained vasodilation, or mediators such as bradykinin, nitric oxide synthase, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)1. HAPE is a noncardiogenic pulmonary edema resulting from increased sympathetic nervous system activity, endothelial dysfunction, and hypoxemia1.

The Lake Louise AMS score is a tool used by researchers to diagnose and to score the severity of AMS6. Symptoms of AMS are often nonspecific and include headache, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, weakness, and fatigue5,1. Peripheral edema, including facial swelling similar to angioedema, is not a symptom of AMS per the Lake Louise criteria, though it has been reported to occur with AMS4.

Angioedema is most often characterized by an abrupt and short-lived swelling of the skin and mucous membranes2. It most commonly leads to facial swelling of the lips and tongue. Angioedema is a result of mast cell-mediated and bradykinin-mediated reactions. These reactions can lead to manifestations of recurrent angioedema in spontaneous or inducible urticaria, congenital hereditary angioedema, or acquired angioedema due to pharmacotherapy2. Of note, inducible urticaria can be triggered by physical stimuli such as skin contact with cold or pressure2. These subtypes are known as cold urticaria and pressure urticaria, respectively. A study on cold urticaria demonstrated that approximately 23% of patients developed angioedema of the lips, tongue and/or pharynx after consuming cold/ice-cold food or drinks2.

The involvement of vasodilatory mediators such as bradykinin in the pathophysiology of high-altitude illness, along with known triggers for inducible urticaria such as cold and pressure, serve as a proposed explanation for the manifestation of angioedema of the lips at high altitude.

Conclusion

Angioedema of the lips is an unreported/underreported reaction to high altitude. While high-altitude illness and its associated disorders have been heavily documented, this reaction has never been described in medical literature as a result of altitude. The involvement of vasodilatory mediators such as bradykinin in the pathophysiology of high-altitude illness, along with cold and pressure serving as known triggers for inducible urticaria, together serve as a proposed explanation of for the manifestation of angioedema of the lips at high altitude.

Complete Visual Timeline

References

- Rodway GW, Hoffman LA, Sanders MH. High-altitude-related disorders–Part I: Pathophysiology, differential diagnosis, and treatment. Heart Lung. 2003;32(6):353-359. doi:10.1016/j.hrtlng.2003.08.002

- Buttgereit T, Maurer M. Klassifikation und Pathophysiologie von Angioödemen [Classification and pathophysiology of angioedema]. Hautarzt. 2019;70(2):84-91. doi:10.1007/s00105-018-4318-z

- Maltseva N, Borzova E, Fomina D, et al. Cold urticaria – What we know and what we do not know. Allergy. 2021;76(4):1077-1094. doi:10.1111/all.14674

- Gill S, Walker NM. Severe facial edema at high altitude. J Travel Med. 2008;15(2):130-132. doi:10.1111/j.1708-8305.2008.00192.x

- Garrido E, Botella de Maglia J, Castillo O. Acute, subacute and chronic mountain sickness. Rev Clin Esp (Barc). 2021;221(8):481-490. doi:10.1016/j.rceng.2019.12.009

- Roach RC, Hackett PH, Oelz O, et al. The 2018 Lake Louise Acute Mountain Sickness Score. High Alt Med Biol. 2018;19(1):4-6. doi:10.1089/ham.2017.0164