Jesse Dalton, DO

Ashley Lauria, DO

Kent Hospital Emergency Medicine Residency

Abstract

Introduction

Renal infarction is a rare, but clinically important diagnosis due to its significant morbidity and mortality. Atrial fibrillation is a major risk factor for thromboembolic disease that can lead to renal infarction.

Case Presentation

We present a 70-year-old female with a history of atrial fibrillation and aortic valve replacement, who developed an acute renal infarction during her stay in the Emergency Department with complications that eventually led to her death.

Conclusion

Renal infarction is an easily missed diagnosis due to its clinical presentation mimicking common abdominal complaints. It is important for clinicians to keep renal infarction on their differential for patients who present with complaints of flank or abdominal pain and have risk factors for thromboembolic disease.

Introduction

Renal infarction is a rare, but serious diagnosis frequently missed in the Emergency Department due to its often-similar presentation to other more common conditions such as nephrolithiasis or pyelonephritis. Symptoms typically seen with acute renal infarction include flank or abdominal pain frequently associated with nausea, vomiting, and fever.

The main causes of renal infarction include cardioembolic disease, renal artery injury, hypercoagulable states, and idiopathic renal infarction.1,3 Atrial fibrillation is a commonly identified cause of cardioembolic disease, along with cardiomyopathy, endocarditis, and artificial valve thrombi.1

Contrast- enhanced computed tomography (CT) is the preferred initial method for diagnosing renal infarction; the classic finding is a wedge-shaped perfusion defect.2 Common laboratory findings include elevated lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), leukocytosis, elevated C-reactive protein (CRP), elevated creatinine levels, and hematuria on urinalysis.1,2

Here, we report a case of a 70-year-old female who presented to the Emergency Department complaining of diffuse abdominal pain. Her initial CT scan was normal. However, 20 hours later, she acutely decompensated and repeat CT scan showed acute renal infarction associated with perirenal hemorrhage.

Case Report

A 70-year-old female with a past medical history of endocarditis, atrial fibrillation previously on rivaroxaban which was discontinued secondary to gastrointestinal bleeding, left atrial appendage closure device, aortic stenosis status post transcatheter aortic valve replacement, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, congestive heart failure, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, and gastroesophageal reflux disease who presented to the emergency department complaining of diffuse abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and muscle aches for 24 hours prior to arrival. On initial evaluation, the patient was hemodynamically stable and afebrile. Her exam was remarkable for an elderly woman who appeared in moderate distress and had a distended abdomen with moderate right upper quadrant tenderness to palpation. Her electrocardiogram showed a normal sinus rhythm without evidence of ischemic changes. Initial laboratory results showed mild leukopenia of 3.5×103/mcL, 18% bandemia, mild acute kidney injury with creatinine 1.38mg/dL (baseline 0.96mg/dL), elevated transaminases (AST 120IU/L, ALT 78IU/L), and elevated lactate of 3.7mmol/L. A rapid COVID-19 nasopharyngeal swab was obtained and was negative. A CT of the abdomen and pelvis with intravenous contrast was performed and revealed hepatomegaly, mild splenomegaly, mild periportal lymphadenopathy, and a small ventral infra-umbilical hernia without evidence of incarceration (Figure 1). The patient was treated symptomatically with a liter of intravenous (IV) isotonic fluids, IV ondansetron, and IV acetaminophen. Due to the patient’s multiple laboratory abnormalities and persistent symptoms, she was admitted to the hospital for further observation.

Figure 1. Initial CT abdomen and pelvis with IV contrast showing hepatomegaly, mild splenomegaly, mild periportal lymphadenopathy

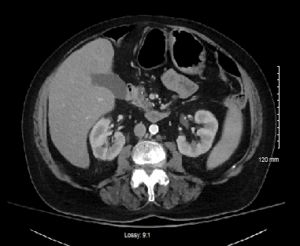

The patient remained in the emergency department pending hospital bed availability for approximately 20 hours when she suddenly decompensated. She became hypotensive, tachycardic, hypoxic, altered, and her abdomen became distended. She was intubated for decreased mental status. A right internal jugular central venous catheter was placed and she was started on norepinephrine. A repeat CT scan of her abdomen was performed, which showed a large area of perirenal hemorrhage which extended above and below the left kidney with patchy enhancement throughout the kidney, suggestive of infarction (Figure 2). The patient was taken for emergent left renal artery embolization by interventional radiology and transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU) for further management.

Figure 2. Repeat CT abdomen and pelvis with IV contrast approximately 20 hours after initial CT scan now with a large area of perirenal hemorrhage which extends above and below the left kidney with patchy enhancement throughout the kidney suggestive of infarction

Upon arrival in the ICU, the patient remained hypotensive requiring vasopressors. Repeat laboratory results were significant for a lactic acid of 15.1mmol/L, hemoglobin of 6.2g/dL, and platelets of 36×103/mcL. She was started on a bicarbonate infusion for her acidosis and she was transfused three units of packed red blood cells, two units of fresh frozen plasma, and one unit of platelets. Blood cultures obtained on initial arrival in the emergency department both resulted positive for methicillin sensitive Staphylococcus Aureus. Nafcillin antibiotic therapy was initiated. A transthoracic echocardiogram was performed and showed an ejection fraction of 65-70%, trace mitral and tricuspid regurgitation, and a bioprosthetic aortic valve without evidence of vegetation.

On day two of admission, her abdominal distension continued to worsen and a non- contrast enhanced CT of the abdomen was performed, showing the left infracted kidney with persistent stable retroperitoneal hemorrhage, persistent contrast in the parenchyma of the right kidney. Additionally, it showed evidence of probable splenic infarct, not previously seen on prior imaging studies.

The urology and general surgery services were consulted and determined she was not a surgical candidate for nephrectomy or splenectomy due to hemodynamic instability despite vasopressor support. The patient was anuric and her creatinine continued to rise daily. She eventually required hemodialysis on hospital day three for anuria and increasing ventilator oxygen requirements, likely secondary to fluid overload.

The patient had a transesophageal echocardiogram performed on hospital day five, which showed ejection fraction of 70%, left ventricular hyperdynamic systolic function, severe left atrial enlargement, moderate mitral regurgitation, and no evidence of endocarditis. The patient continued to deteriorate daily despite antibiotic therapy, continued vasopressors, and dialysis. On hospital day six, her family decided to pursue comfort measures and she died later that evening.