Dhimitri Nikolla, DO, PGY-3

ACOEP-RSO President

AHN Saint Vincent Hospital, Erie, PA

INTRODUCTION

With the widespread availability of intraosseous (IO) needles and ultrasound, emergent central lines placed with landmark-guidance (LG) are becoming a thing of the past. While IO access is faster and ultrasound guided central lines have higher success rates with fewer complications than LG central lines, IO devices or ultrasounds are not always immediately available [1-5].

In these scenarios, LG central lines are often our only option in the critically-ill patient who requires emergent and reliable vascular access. While every patient is different and the best location of the central line is patient specific, the LG femoral central line is likely the most versatile as it is a compressible site and does not require Trendelenburg positioning of the patient. As this vital skill seems to be performed less and less frequently, here are some tips to help with the hardest part of the procedure: getting flash!

POSITIONING

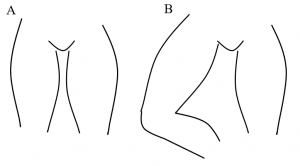

Like any procedure, positioning is critical! Placing the patient in reverse Trendelenburg can increase the cross-sectional area and exposed width of the femoral vein, and it may help mitigate any respiratory distress your patient may be in [6-12]. If a large pannus is obstructing the insertion site, be sure to have someone manually retract it or use tape to anchor it to the bed rail. Lastly, flexion and external rotation of the ipsilateral hip or the “frog-leg position” is critical (Figure 1).

Figure 1 displays a patient with neutral hips (A) and a patient with the right hip flexed with external rotation, the “frog-leg position” (B).

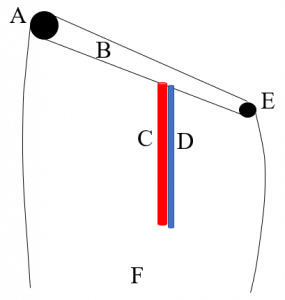

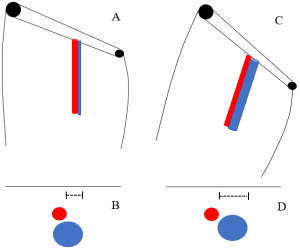

As seen in Figure 2, the femoral vein runs medial to the femoral artery. However, the vein is usually deep to the artery and often can sit directly underneath the artery. Flexion and external rotation of the ipsilateral hip can help expose the vein giving the physician a larger target (Figure 3).

Figure 2 displays the pertinent landmarks needed to place a landmark-guided femoral central line including the anterior superior iliac spine (A), inguinal ligament (B), femoral artery (C), femoral vein (D), pubic tubercle (E), and the right distal thigh for orientation (F).

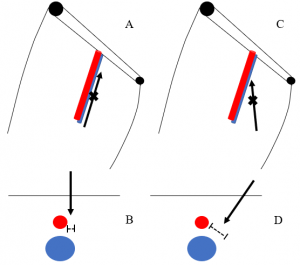

Figure 3 displays the orientation of the femoral artery and vein with neutral hip positioning in the coronal plane (A) and axial plane (B) as well as their orientation with hip flexion and external rotation in the coronal plane (C) and axial plane (D). Note the lengths of the dotted lines in images B and D revealing the increased exposure of the femoral vein with hip flexion and external rotation.

INSERTION SITE AND ANGLE

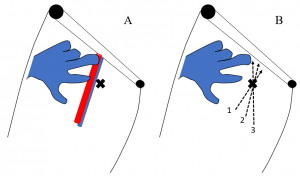

The insertion site is classically taught as 1 cm medial to the site of maximal pulsations and about 1-2 cm distal to the inguinal ligament (Figure 4A) [13,14]. The finder needle is inserted through the skin and subcutaneous tissues with slight aspiration of the attached syringe until an observed flash or aspiration of dark venous blood is obtained. A trajectory more medial than expected should be taken first followed by withdrawing the needle until the tip is just below the skin and re-inserting it with a more lateral approach in the direction of the femoral artery (Figure 4B). The angle of insertion with respect to the skin surface is about 45 degrees [14].

Figure 4 displays the finder needle insertion site with respect to the landmarks and palpable pulsations of the femoral artery (A) as well as the trajectory of finder needle with each attempt 1-3 (B).

Often this technique is not enough to get a flash. Some other maneuvers that may help include aspirating as the finder needle is withdrawn and intermittently aspirating the syringe as opposed to continuously aspirating. Frequently, the vein collapses as the finder needle is inserted; therefore, the finder needle can be inserted through the anterior and posterior walls of the vein without obtaining a flash. As the finder needle is withdrawn, the vein re-expands and as the tip of the needle is withdrawn through the lumen of the vein, a flash can then be obtained. Similarily, intermittently aspirating as opposed to continuously aspirating may prove more successful as you may avoid aspirating the wall of the vein into your bevel further preventing a flash. These are especially useful in the hypotensive patient where the vein is significantly more collapsible.

Lastly, sometimes none of these techniques work because the femoral vein is simply underneath the femoral artery. If this is suspected, try inserting the finder needle slightly more medial, about 2 cm medial to pulsations and advancing the finder needle below the artery (Figure 5). A more medial insertion site with a more lateral trajectory can often improve the chances of accessing the femoral vein, especially if the vein sits below the artery.

Figure 5 displays difference in exposed femoral vein (dotted lines) between an insertion site closer to the artery with a more medial trajectory in the coronal plane (A) and axial plane (B) compared a more medial insertion site with a more lateral trajectory in the coronal plane (C) and axial plane (D). Note the lengths of the dotted lines in images B and D revealing the increased exposure of the femoral vein with the more medial insertion site.

CONCLUSION

While this is not a comprehensive review of the LG femoral central line, these tips should help you get a flash during your next emergent blind “fem” line!

REFERENCES

- Leidel BA, Kirchhoff C, Bogner V, et al. Comparison of intraosseous versus central venous vascular access in adults under resuscitation in the emergency department with inaccessible peripheral veins. Resuscitation. 2012 Jan;83(1):40-5. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2011.08.017. Epub 2011 Sep 3.

- Airapetian N, Maizel J, Langelle F, et al. Ultrasound-guided central venous cannulation is superior to quick-look ultrasound and landmark methods among inexperienced operators: a prospective randomized study. Intensive Care Med. 2013 Nov;39(11):1938-44. doi: 10.1007/s00134-013-3072-z. Epub 2013 Sep 12.

- Prabhu MV1, Juneja D, Gopal PB, et al. Ultrasound-guided femoral dialysis access placement: a single-center randomized trial. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010 Feb;5(2):235-9. doi: 10.2215/CJN.04920709. Epub 2009 Dec 3.

- Brass P, Hellmich M, Kolodziej L, et al. Ultrasound guidance versus anatomical landmarks for internal jugular vein catheterization. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Jan 9;1:CD006962. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006962.pub2.

- Balls A, LoVecchio F, Kroeger A, et al. Ultrasound guidance for central venous catheter placement: results from the Central Line Emergency Access Registry Database. Am J Emerg Med. 2010 Jun;28(5):561-7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2009.02.003.

- Kim W, Chung RK, Lee GY, et al. The effects of hip abduction with external rotation and reverse Trendelenburg position on the size of the femoral vein; ultrasonographic investigation. doi: 10.4097/kjae.2011.61.3.205

- Ibañez J, Raurich JM. Normal values of functional residual capacity in the sitting and supine positions. Intensive Care Med. 1982;8(4):173-177. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2011 Sep; 61(3): 205–209.

- Hoste EA, Roosens CD, Bracke S, et al. Acute effects of upright position on gas exchange in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. J Intensive Care Med. 2005;20(1):43-49.

- Richard JC, Maggiore SM, Mancebo J, Lemaire F, Jonson B, Brochard L. Effects of vertical positioning on gas exchange and lung volumes in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Intensive Care Med. 2006;32(10):1623-1626.

- Solis A, Baillard C. Effectiveness of preoxygenation using the head-up position and noninvasive ventilation to reduce hypoxaemia during intubation. Ann Fr Anesthèsie Rèanimation. 2008;27(6):490-494.

- Van Beers F, Vos P. Semi-upright position improves ventilation and oxygenation in mechanically ventilated intensive care patients. Crit Care. 2014;18(Suppl 1): P258.

- Ceylan B, Khorshid L, Günes¸ ÜY, Zaybak A. Evaluation of oxygen saturation values in different body positions in healthy individuals. J Clin Nurs. 2016;25(7-8):1095-1100.

- Bannon MP, Heller SF, Rivera M. Anatomic considerations for central venous cannulation. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2011;4:27–39.

- Tintinalli, Judith E.,, et al. Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide. Eighth edition. New York: McGraw-Hill Education, 2016. p. 202-204.