Dhimitri Nikolla, DO

AHN Saint Vincent Hospital, Erie, PA

CASE

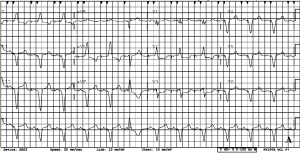

An 86 year-old female with a past medical history of chronic congestive heart failure with a dual-chamber pacemaker, hypertension, severe mitral regurgitation, and dementia was sent to the emergency department (ED) by family via ambulance with reports of confusion, hallucinations, and poor appetite for one week. The patient was a poor historian and family was not present initially to provide further history. On examination, her vital signs were normal. She was alert but confused without a focal motor or sensory deficit. She had a systolic ejection murmur with some bibasilar crackles, but no peripheral edema. Her electrocardiogram (ECG), as well as previous, is displayed in Figure 1.

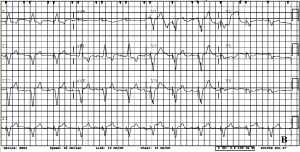

Figure 1 displays the patient’s electrocardiogram (A) at presentation to the emergency department with a paced rhythm at 75bpm in a right bundle branch block pattern with a PVC and appropriately discordant ST segments except for lead V3 where there is new concordant ST segment depression compared to the previous electrocardiogram (B).

Her initial troponin in the ED was 6.20 ng/ml. She was given aspirin, nitroglycerin, and heparin in the ED. Just prior to admission her family arrived and confirmed the history from EMS as well as described marked weakness in that the patient was having more difficulty ambulating. They denied the patient experiencing any chest pain or shortness of breath.

DISCUSSION

Patients often present to the ED with nonspecific symptoms making a focused evaluation nearly impossible. Since the classic description of cardiac chest pain is not sensitive nor predictive of acute myocardial infarction (AMI) (1), most adult patients presenting to the ED with any chest pain will likely be evaluated for AMI. Unfortunately, many patients may not even experience chest pain at all in the setting of AMI, particularly women and the elderly. Women with AMI are more likely than men to present without chest pain and carry a higher mortality (2-3). Similarly, elderly patients can present with a variety of symptoms; one study of elderly patients with STEMI found chief complaints of presyncope or fall 15.7% of the time, gastrointestinal symptoms 9.8%, impaired condition 6.7%, and delirium 5.0% (4). Emergency providers should have a high suspicion for AMI in women and the elderly despite a lack of chest pain.

Similarly, an underlying paced rhythm can make interpretation of the ECG difficult. The rule of appropriate discordance describes the expected discordance of the ST segment one would expect to see in a bundle branch block or paced rhythm (5). There is no definitive rule or method to differentiate between ST segment changes from an underlying paced rhythm and possible AMI. However, the following ST changes are highly suspicious for AMI (6):

- ≥5mm of ST segment elevation in leads with a generally negative deflection (Excessive Discordance).

- ≥1mm of ST segment elevation in a lead with a generally positive deflection (Concordance).

- ≥1mm of ST segment depression in a leads V1-V3 or leads with a generally negative deflection (Concordance).

What is concordance vs discordance on an electrocardiogram?

|

CASE CONCLUSION

The patient was admitted to the intensive care unit. Due to her multiple comorbidities, medical therapy alone was recommended by the cardiology team. She had an echocardiogram that revealed an ejection fraction of <30% with diffuse hypokinesis. Although, clinically, she did not appear to be in heart failure. Her subsequent troponin levels gradually declined. She was continued on heparin for three days and was discharged to a rehabilitation facility seven days later with prescriptions to continue her aspirin, carvedilol, and atorvastatin.

REFERENCES

- Body R, Carley S, Wibberley C, et al. The value of symptoms and signs in the emergent diagnosis of acute coronary syndromes. Resuscitation. 2010 Mar;81(3):281-6.

- Khan NA, Daskalopoulou SS, Karp I, et al. GENESIS PRAXY Team. Sex differences in acute coronary syndrome symptom presentation in young patients. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(20):1863–71.

- Canto JG, Rogers WJ, Goldberg RJ, et al. NRMI Investigators. Association of age and sex with myocardial infarction symptom presentation and in-hospital mortality. JAMA. 2012;307(8):813–22.

- Grosmaitre P, Le Vavasseur O, Yachouh E, et al. Significance of atypical symptoms for the diagnosis and management of myocardial infarction in elderly patients admitted to emergency departments. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 2013 Nov;106(11):586-92.

- Rosner MH, Brady WJ. The electrocardiographic diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction in patients with ventricular paced rhythms. Am J Emerg Med. 1999 Mar;17(2):182-5.

- Sgarbossa EB, Pinski SL, et al. Early electrocardiographic diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction in the presence of ventricular paced rhythm. Am J Cardiol. 1996 Feb 15;77(5):423-4.