Timothy Bikman , OMS IV, West Virginia School of Osteopathic Medicine

Terrance McGovern DO, MPH, PGY-IV, St. Joseph’s Regional Medical Center, Department of Emergency Medicine, Paterson, NJ

Anthony Catapano, DO, St. Joseph’s Regional Medical Center, Department of Emergency Medicine, Paterson, NJ

Case Report

A 6-year-old female presented with a two-day history of abdominal pain after being referred by her pediatrician for evaluation of “splenomegaly.” The patient had been complaining of constipation for the past six days along with a few episodes of nausea and vomiting. On physical examination, a firm, non-tender mass was palpated extending at least 10 cm below the left costal margin.

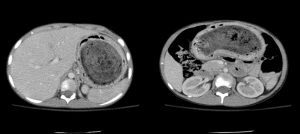

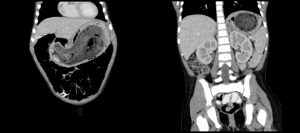

The patient’s labs revealed a significant iron deficiency anemia with a hemoglobin of 6.3g/dL and hematocrit of 23%. The ultrasound of the spleen revealed a normal spleen without any evidence of splenomegaly or renal masses. Abdominal x-rays showed a large density that was possibly a distended stomach (Image 1). To further evaluate the mass, a CT of the abdomen and pelvis (Images 2 & 3) was obtained which revealed a mass-like entity that completely filled the stomach, consistent with a large gastric bezoar.

On subsequent questioning, the patient’s mother mentioned that she has noticed her daughter peeling and eating pieces of Velcro from her book bag and lunch box; similar to her sister who developed trichotillomania around the same age. After evaluation by pediatric gastroenterology and surgery, the decision was made to proceed with surgical removal of the mass due to its large size that would have made endoscopic removal difficult. The patient underwent an exploratory laparotomy and a 20 x 5 x 7 cm mass was removed from the stomach which was composed of predominantly hair and other textile like material.

Image 1 is an Abdominal/KUB AP X-ray revealing a large soft tissue density with numerous tiny lucencies is seen within the left abdomen.

Image 2

Image 3

Images 2 & 3 are from the patient’s CT Abdomen and Pelvis with oral and IV contrast revealing ingested material filling almost the entirety of the stomach most consistent with a large bezoar.

Pediatric gastroenterology evaluated the patient and considered her for endoscopic removal, but determined that due to the size of the bezoar, the procedure would likely be unsuccessful. Therefore, Pediatric surgery was consulted and the patient underwent an exploratory laparotomy for removal of the large gastric bezoar. The pathology report revealed a 20.5 x 7 x 7cm mass composed of mostly hair and some other additional material.

Discussion

A gastric bezoar is an accumulation of indigestible material commonly found as a hard mass in the stomach. Bezoars can be subcategorized into four distinct types based on the primary material composing the mass. The four subcategories are phytobezoars (plant material), trichobezoars (hair), pharmacobezoars (medications), or other (1).

The epidemiology of bezoars depends on a number of factors including age, sex, and comorbid conditions. In adults, phytobezoars are most commonly found in middle-aged men (40-50 years old). However, women in their 20’s more commonly have trichobezoars, and have associated psychiatric disorders. These masses can commonly reoccur if the underlying cause is not properly addressed. Other risk factors include problems that affect gastric motility (medications, surgeries, and medical diseases), gastric emptying abnormalities, dehydration, and anatomic anomalies (1).

Once a patient is found to have a bezoar, appropriate management is dependent on the underlying cause and other contributing factors. There are three primary techniques for removing a bezoar. For small uncomplicated bezoars, prokinetic agents like metoclopramide, and chemical dissolution agents can be used. The second, the most commonly used technique is endoscopic removal. Lastly, when the mass is too large and/or the clinical situation is more complicated, abdominal laparotomy is used to surgically remove the mass (1,2).

Removal of the bezoar is only one step in what is often a multifactorial program that requires an equally dynamic approach to management. This was the case for our patient. Our patient was young, had a very large mass, was experiencing severe anemia, and had some underlying psychiatric issues leading to trichotillomania/pica. To properly address this complicated situation a multi-specialty team was organized. This team was composed of general pediatrics, pediatric gastroenterology, pediatric surgery, and pediatric psychiatry. Together they effectively and appropriately managed this pediatric patient’s anemia, bezoar removal, general medical health, and underlying psychological conditions to properly care for her acutely and prevent future occurrences.

In emergency medicine, we are constantly presented with patients who present with what seems to be a very simple diagnosis and associated work-up, but on further investigation there is the possibility of a much more ominous pathological process present. We as emergency medicine professionals cannot afford to oversimplify any case. Our differentials must be broad, especially in regards to atypical presentations and potentially dangerous pathologic processes (3). In the case of gastric bezoars, a missed diagnosis can lead to many serious complications such as bleeding, perforation, and small bowel obstruction. These complications can be found in the young and old alike. Gastric Bezoars should be considered when patients of any age, present to the emergency department complaining of abdominal pain, weight loss, anemia, and/or unexplained abdominal mass (2). A thorough ingestion history is warranted and will aide in making a diagnosis and appropriate management plan. Imaging may include plain films, ultrasound, or CT scans. A multi-specialty approach is often necessary to properly manage acute cases and prevent future recurrences.

References

- Gelrud D, Guelrud M. “Gastric Bezoars.” UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/gastric-bezoars?source=search_result&search=gastric%20bezoar&selectedTitle=1~13 (Accessed: May 14, 2017)

- Castle SL, Zmora O, Papillon S, et al. Management of Complicated Gastric Bezoars in Children and Adolescents. Isr Med Assoc J. 2015;17(9):541-4.

- Lynch KA, Feola PG, Guenther E. Gastric trichobezoar: an important cause of abdominal pain presenting to the pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2003;19(5):343-7